🧮 Energy transition or addition ?

Diving into 2023 energy statistics to assess progress on the energy transition.

The energy transition is about eliminating fossil sources from the electricity mix while electrifying everything to reduce our problematic oil consumption (not olive oil, of course, the oil you put in your car!).

In this newsletter, we often explore technological advancements and other enablers of the energy transition, but today we dive into numbers. With the release of 2023's energy statistics, now largely unaffected by COVID-19, we can assess the actual progress of the energy transition using the latest data.

State of Global Energy in 2023

Reviewing the recently released 73rd edition of the Statistical Review of World Energy, it’s clear that fossil fuels, at a global level, are not dead yet:

Crude oil consumption hit a record of 100 million barrels/day, a 2.6% year-over-year (YOY) growth, above its 1.1% consumption growth average of the last decade.

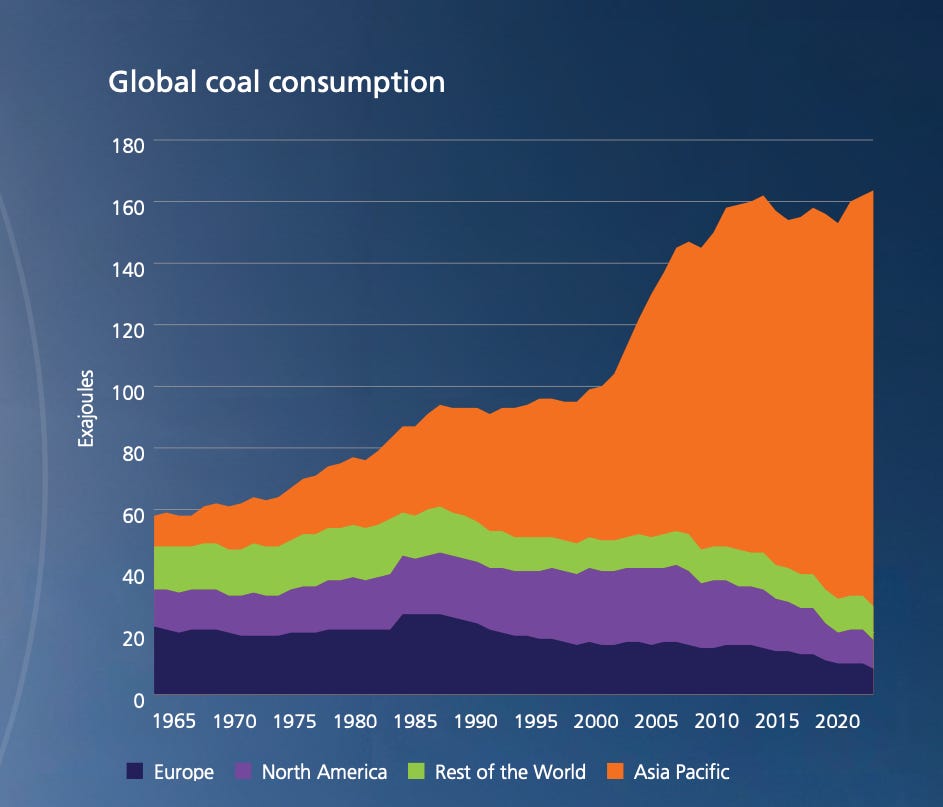

Coal consumption grew 1.6% YOY, above its 0.2% average of the last decade.

Gas consumption was flat this year, but its decade growth rate of 1.9% is higher than both coal and oil.

However, renewables and clean energy generation also put on a show of their own:

Nuclear power grew at 2.2% YOY, above the 1.0% average of the last decade.

Wind generation grew at 10.3% YOY, below its 13.9% average of the last decade.

Solar grew at 24.2% YOY, below its 28.0% average of the last decade.

Hydro reduced by -1.9% YOY, below its 1.1% average of the last decade.

The electricity generation sector as a whole grew at 2.5% YOY, 25% faster than the primary energy sector, suggesting a continuing trend of electrification.

To put these numbers into perspective, we are in both an energy transition and addition scenario globally. While renewable energy sources are rapidly increasing and replacing some fossil fuels, we continue to increase our consumption of coal, oil, and gas each year.

Will the energy transition truly curb fossil fuel use or will a rebound effect—where increased energy availability leads to increased consumption— occur? To gain insights, we look at the data breakdown by region.

Breaking it down by region

We saw that global oil consumption, in 2023, had a 2.2% YOY growth. Breaking it down by region, Europe’s consumption fell by nearly 1%, demand in North America grew by 0.8%, and the Asia Pacific region, which includes China and India, consumption grew by 5%! (respectively China and India’s oil consumption grew by 10.7% and 4.6%).

A similar trend is observed with coal, the most polluting primary energy source. Consumption in Europe and North America has been declining for the last four decades, whereas China and India now consume more than 69% of the world’s coal (56% and 13% share, with 4.7% and 9.8% YOY growth, respectively).

Global coal consumption by region, 2023 Statistical Review of World Energy, Energy Institute

It seems like most of the energy addition is happening in the developing world, highlighting a significant shift in global energy dynamics. Let’s dig deeper.

Trying to make sense of it all

It’s not easy to find heuristics to explain the complex dynamics of energy, with each country having its specificity. Acknowledging this, my key take-away on the transition vs addition dilemma revolves around energy-intensive manufacturing output & capital availability. But first let’s broadly categorise countries in terms of perceived transition speed and energy addition:

Countries categorised by GDP/capita (rich > 40’000$, middle >10’000$, and poor < 10’000$), and total manufacturing output, assessed on simplified energy transition speed (average growth over the last decade of renewable generation and electrification), and energy addition (primary energy growth over the last decade).

This leads me to a simplified hypothetical heuristic, that all countries are transitioning, but that the industrial-heavy countries, except the rich ones, are also growing their energy consumption fast. Behind this simplified heuristic, not taking into account demographics, for example, are the concepts of off-shoring and investing in the transition.

First energy-intensive processes, such as steel making, the chemical industry or even solar panel manufacturing, are driven by the price of energy and carbon. With a lot of other less value-add manufacturing, we have off-shored these industries, increasing the energy needs of middle and poor industrial-heavy countries. Combined with increased demand from lifting more people out of poverty, this explains the addition of energy consumption in middle and low GDP/capita industrial-heavy countries, and flattening to reduction in rich industrial-heavy countries.

Secondly, the energy transition is capital intensive, because most of the cost of a solar and wind farm comes from the construction (as opposed to a coal power plant which is relatively cheap upfront but has higher operating costs). This can explain why richer countries can transition faster (due to capital and financing availability), whereas poorer countries can’t afford to spend as much up-front. This would also explain China’s dominance in renewable build-out (being the richest industrial-heavy energy-intensive country). (China’s installed solar capacity grew 55% (!!!) in 2023, now accounting for 43% of the world’s total solar installed capacity.)

In a nutshell

To summarise, by exploring the energy statistics of 2023, we have seen that we are both in an energy transition and addition scenario. We are burning more oil, coal and gas every year, but the build-out and generation of renewables is way faster (5 to 10x) than our fossil fuel increase. We are cleaning up electricity generation from fossil fuels quite fast. Furthermore, electricity generation growth is 25% faster than primary energy consumption, showing we are slowly electrifying everything.

Yet, these trends do not answer an important question: will the transition prevent us from burning all the fossil fuels available, or will we curb our fossil fuel usage?

By breaking down data by regions, we saw that while all countries were transitioning (at different paces), the lower GDP/capita industrial-heavy countries were also growing their energy consumption fast. The poorer the country the more this growing consumption is fossil-based.

Most rich countries are curbing their fossil fuel usage, indicating we could be safe from a rebound effect. However, if this is mainly due to off-shoring, as hypothesized, we should also think about financing the energy transition abroad, as well as reducing demand relying on energy-intensive industries.

I hope this complex dive into energy statistics, and my takeaway, was interesting. You can check out the full 2023 Statistical Review of World Energy here.

From Geneva 🇨🇭,

Jean

PS: Got tips to improve the newsletter or topics you would like me to explore? Reply to this email with your suggestions!