🌪️ Natural Disasters and Climate

The statistics of natural disasters, climate change, and a tale of fat tails.

Every day, we hear about record-breaking floods or intense heat waves, and we often blame climate change. But is there a real connection, and are natural disasters on the rise or is it merely media sensationalism?

In this issue of Seagnal, a newsletter at the intersection of technology and sustainability, we explore the science behind extreme weather events. We'll begin by demystifying the term "one-in-a-hundred-year" events, explaining what it means and how it's used. Then we will study the frequency and intensity of natural disasters, and how well we are adapting to them.

One-in-100-year

A "one-in-100-year" event refers to an event expected to happen once every century at a specific location. For example, the Danube River might be expected to rise by 2 meters once per century on average. So why do we hear about these events so frequently?

First, while a 2 meters rise in the Danube river would be expected to happen only once in a hundred years on average, you would expect a river rise one-in-100 year event to be exceeded somewhere across the globe much more frequently.

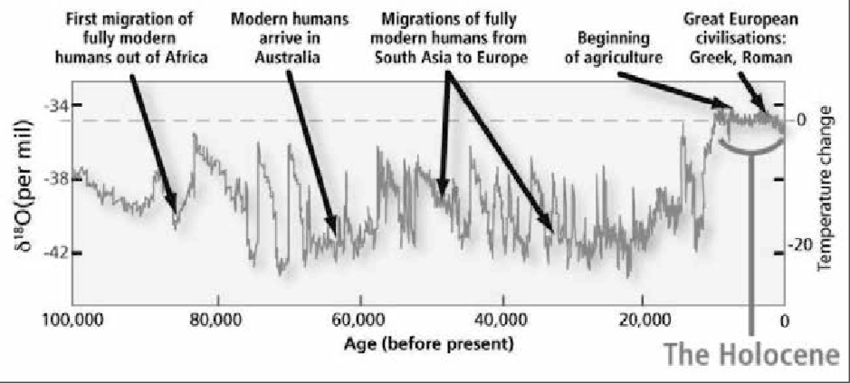

Secondly, the modeled frequency of these events is calculated based on recent historical data, typically covering the last hundred years—a period when the climate was relatively stable. However, with rising temperatures and increasing climate variability, the frequency of these "one-in-100-year" events might be changing!

Temperature change over the last 100,000 years, showing climate stability in the Holocene (IGBP, 2014) source. Extreme event forecasting is based on stable Holocene-era data.

We may hear more often about extreme events, but to truly understand whether this increase is due to a more interconnected and populated world or because of climate change, we need to look at the statistics.

Increased frequency? Really?

If we look first at frequency, there is a clear increase in reported natural disasters. However, it’s hard to assess if this is due to reporting bias or if there are truly more events. The database maintainers, EM-DAT, suggest taking only data from the 2000s which shows less, if any, increase in reported events.

Global reported natural disasters by type, 1970 to 2024, Our World in Data, CC BY 4.0

A tale of fat tails

Frequency is only part of the picture. A single highly catastrophic event, such as the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, which caused 220’000 deaths, can completely change the story.

Events of this nature, where a single occurrence — or outlier — can drastically change the mean of a dataset, are called "fat-tailed distribution". This concept is also referred to as the Pareto law or Power law.

Another example of a power law distribution is wealth. If you take a thousand people and then add Elon Musk to the group the mean will change drastically. This would not be the case if you added a basketball player to the same group and measured the average height (which follows a normal distribution).

“If you thought earthquakes had a normal distribution, such a tail event [as the 2011 Fukushima earthquake] would be equivalent to observing a twenty-foot-tall woman striding down the street” - The Economics of Tail Events with an Application to Climate Change (2011), William D. Nordhaus

Reasearchers that focused on the economical impact of these outliers, using methods fit to assess power law distributions found sharp increase in the economic damages of extreme natural disasters (including in temperate zones). The more extreme the events the bigger the correlation — i.e catastrophic events are getting costlier.

Their results are also consistent with an upwardly curved, convex damage function. This implies that as the intensity of catastrophic events increases, the incremental damage also increases at an accelerating rate.

We find empirical support for the use of a convex, upwardly curved damage function in integrated climate-economics models […] and for the importance of tailrisks. Evidence for sharp increase in the economic damages of extreme natural disasters, PNAS 2019.

On the bright side, while these events are costing us more, we have also managed to greatly reduce the number of deaths — likely due to better monitoring, lower vulnerabilities, better response, and cooperation.

Despite slightly higher frequencies and strength, in recent decades, extreme droughts have become less fatal. So have extreme floods, but only in rich countries. We observed an increasing polarization between poor and rich areas of the world also for casualties caused by storms […] extreme temperature events have become more deadly in poor and rich countries alike. Evidence for sharp increase in the economic damages of extreme natural disasters, PNAS 2019.

What does this mean practically?

Returning to our initial question on the correlation between climate change and increased extreme weather events, we find the current data to be inconclusive. While there are more reported events and greater economic impacts from outliers, we also have a larger population and more assets at risk. Despite not fully answering the question, we can observe the following:

One-in-100-year events occur more frequently than we might expect, primarily due to the nature of probabilities.

Our models are based on recent historical data, which may be inadequate for predicting a rapidly changing climate and fat tail distributions.

Although there is an increase in reported natural disasters, there is no consensus on whether this rise is directly due to climate change.

Advances in technology and cooperation have improved our ability to reduce the death toll from most natural disasters, though heatwaves remain an exception.

As the intensity of catastrophic events increases, the resulting damage also rises at an accelerating rate, described by a convex damage function.

This exploration into natural disasters and extreme weather events highlights human ingenuity and the power of collaboration. While the frequency and intensity of these events may be on the rise, our advancements in technology and international cooperation have significantly enhanced our ability to mitigate their impacts and save lives.

🔗 - Check these out

Links related to this article you might enjoy:

Antifragile, by Nassim Taleb, is an excellent book that explores everyday fat-tail distributions and offers insights on how to become more resilient to them.

From Geneva 🇨🇭,

Jean

PS: Got tips to improve the newsletter or topics you would like me to explore? Reply to this email with your suggestions!

Super étude claire et facile à comprendre par les non initiés.

Merci